top 6 mistakes of deep tech startups

=companies =startups

Here are some mistakes

I've seen multiple "deep

tech" startups make. Instead of just covering technical details, I'll

try to generalize to some broadly-useful points.

#1: not researching problems

Most ideas that people

have were proposed 50 years ago in some scientific papers. If an idea has

several papers on it but hasn't been pursued industrially, there are often

good reasons for that. Few people want to say "the line of research I

pursued is a dead end, give up" so the main problems for implementation are

often not mentioned in papers. This information might be hard to get. It

might be hidden in an obscure paper you missed. It might be known to a big

company who pursued that 20 years ago. Still, you have to try to either find

it or figure it out.

Here's an example. If

syngas could be fermented

to chemical products, the economics seem attractive. This has been proposed

for several decades, there are quite a few papers on this, and there are

some new startups trying to do that for more-renewable chemical production.

Those papers generally don't mention that H2 and CO have very low solubility

in water, which makes transfer from bubbles to solution too slow for this to

be economically feasible. (There are bacteria in cow stomachs that convert

hydrogen to things, but that hydrogen is both generated and used

homogeneously, with no transfer between bubbles and solution.)

If you need to know if there's some obscure problem, just asking professors won't usually work. Some options are:

- finding

"Challenges of X" review papers (if any exist) and being able to tell how

serious those problems are

- being an expert on that topic, checking many

published papers, and trying to read between the lines

- seeing if professors are joining (or interested in

joining) startups

- finding a former PhD student who studied that then

left that field

- finding a grumpy old man who worked for a related

company as an engineer for 40 years

- asking me

#2: inadequate cost analysis

Sometimes people estimate costs from one perspective, get results they like, and then stop there. For example, if you calculate the theoretical minimum energy cost for extracting lithium from seawater, and assume that net costs would be a few times that, that seems like a good business idea. A better approach is to find some other ways to estimate costs, and compare them. For example, the costs of processing seawater in reverse osmosis plants are fairly public information. If you consider costs from that perspective, lithium from seawater seems to be 1000x too expensive, rather than profitable. I think a big reason why many people don't do that is simply that they want the good numbers to be true, so they don't want to check them.

People develop expertise

around what they do, which means most people only understand costs in the

circumstances that they normally work on and think about. Sometimes they're only familiar

with costs in one situation, and wrongly assume that relative costs stay

similar when the situation changes.

Some things are

expensive on a small scale, but cheap on a large scale. Coal

and steel are cheap, but mining coal and making steel on an individual scale

is very expensive. Custom internal software tools are extensively used in

some large companies, but those are more expensive per employee for small

companies. Sometimes a startup founder worked at a large company, and wants

to do things the same way at their startup, but that's not always feasible.

Some things are cheap on a small scale but

expensive on a large scale. For example, palladium is $57000/kg, but

palladium-based catalysts are often used in chemistry labs, and aren't

particularly expensive compared to other chemicals. Catalysts never last

forever, so it's often hard to make money using palladium to make something

worth $1/kg.

The usual term for figuring out if a new idea is economically feasible is "techno-economic analysis". If you want to pursue some new idea from a paper, then see if that's been done already. You should also read a bunch of them until you understand how they're done and what good and bad ones look like.

#3: believing bad scientific papers

People writing scientific papers, grant authorizations, university PR

releases, and science magazines all have incentives to pretend that some new

ideas are useful and important. Usually this is limited to

p-hacking and

lies of omission, but some people go as far as

faking data.

In that linked case, some other researchers tried to replicate the bad

research, failed to get the same results, tried to publish that, and were

rejected from journals because negative results aren't interesting.

Researchers are also often reluctant to contradict someone more prestigious

than they are for political reasons.

Startup founders are usually optimistic. Investors are usually not

highly technical. Over and over, I've seen someone fresh out of college who

wants to solve some problem in the world, sees some papers describing a

putative solution, and decides they want to make a startup based on that

idea, but sometimes their proposal's foundation is made of bad statistics or

lies.

What can you do about this?

- Look for

papers replicating the data. One way to find them is to take your key paper,

find papers citing it, search within them for relevant terms, and look

within those results for people doing the same thing as a starting point. If

a paper seems important, isn't very new, isn't extremely obscure, and doesn't have any

replications or citations, there's probably a problem with it.

- Hire a

professor as a consultant, someone that could work on that but isn't and

doesn't have to care about academic politics much.

- Try to

check key results yourself as soon as you can, instead of just assuming you

have accurate information.

- Have contingency plans, partly because that

makes it psychologically easier to admit that there's a problem. (Don't tell

investors or journalists about them, because they'll think that means you

think your main plan won't work.)

- If you're an investor, figure out the

biggest risks and ask founders to make contingency plans for them, even if

the plan is just "give up".

#4: believing bad charts & numbers

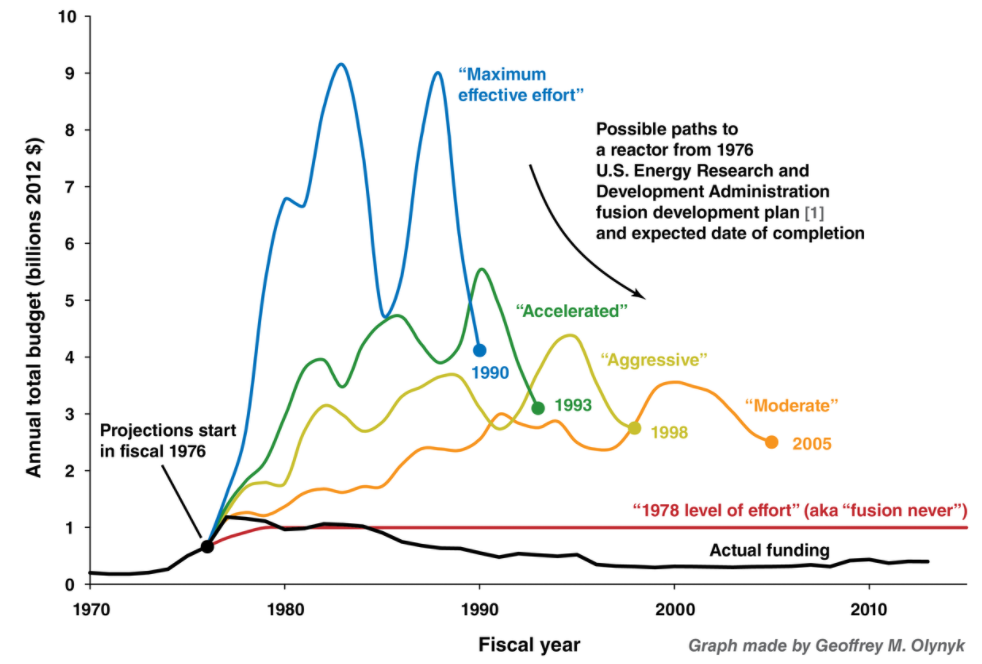

Here's a graph that I've seen several times:

Every so often, people post that and say, "If only we'd spent $100B on fusion research,

we'd be using fusion power right now!" But no, that's just...some lines that

a guy drew in 1976, loosely based on an understanding of tokamaks now known

to be flawed. It's just lines.

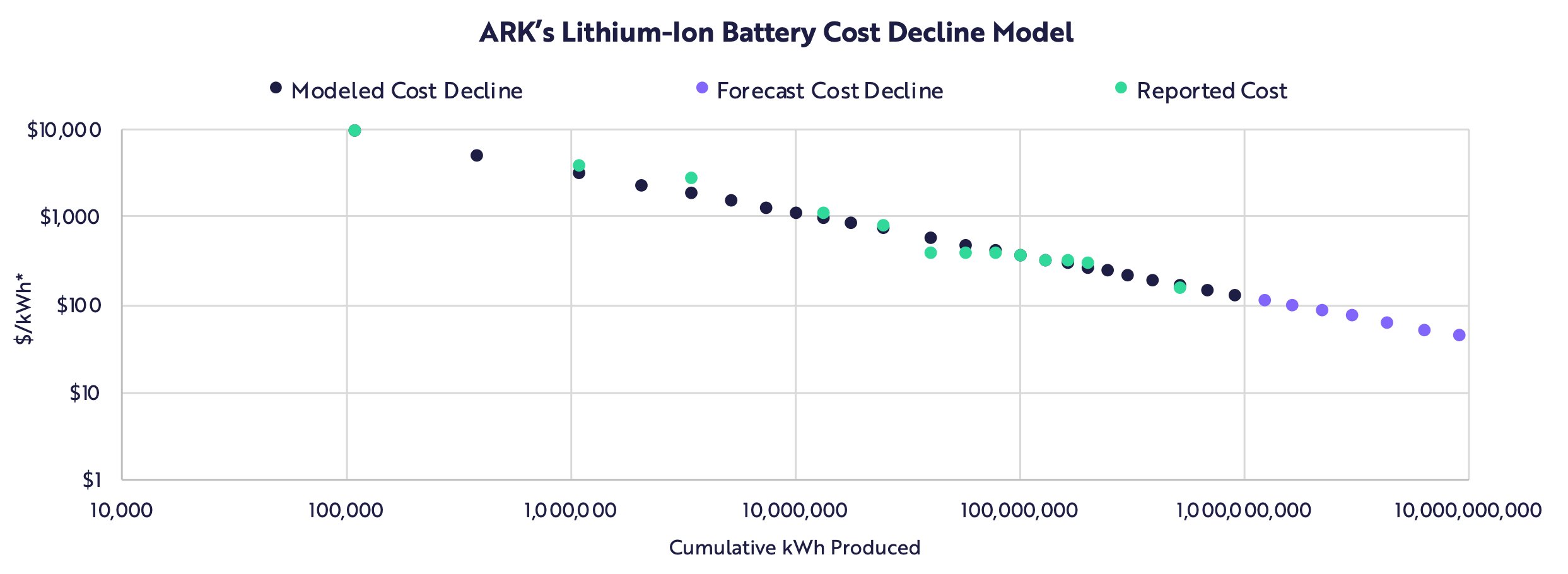

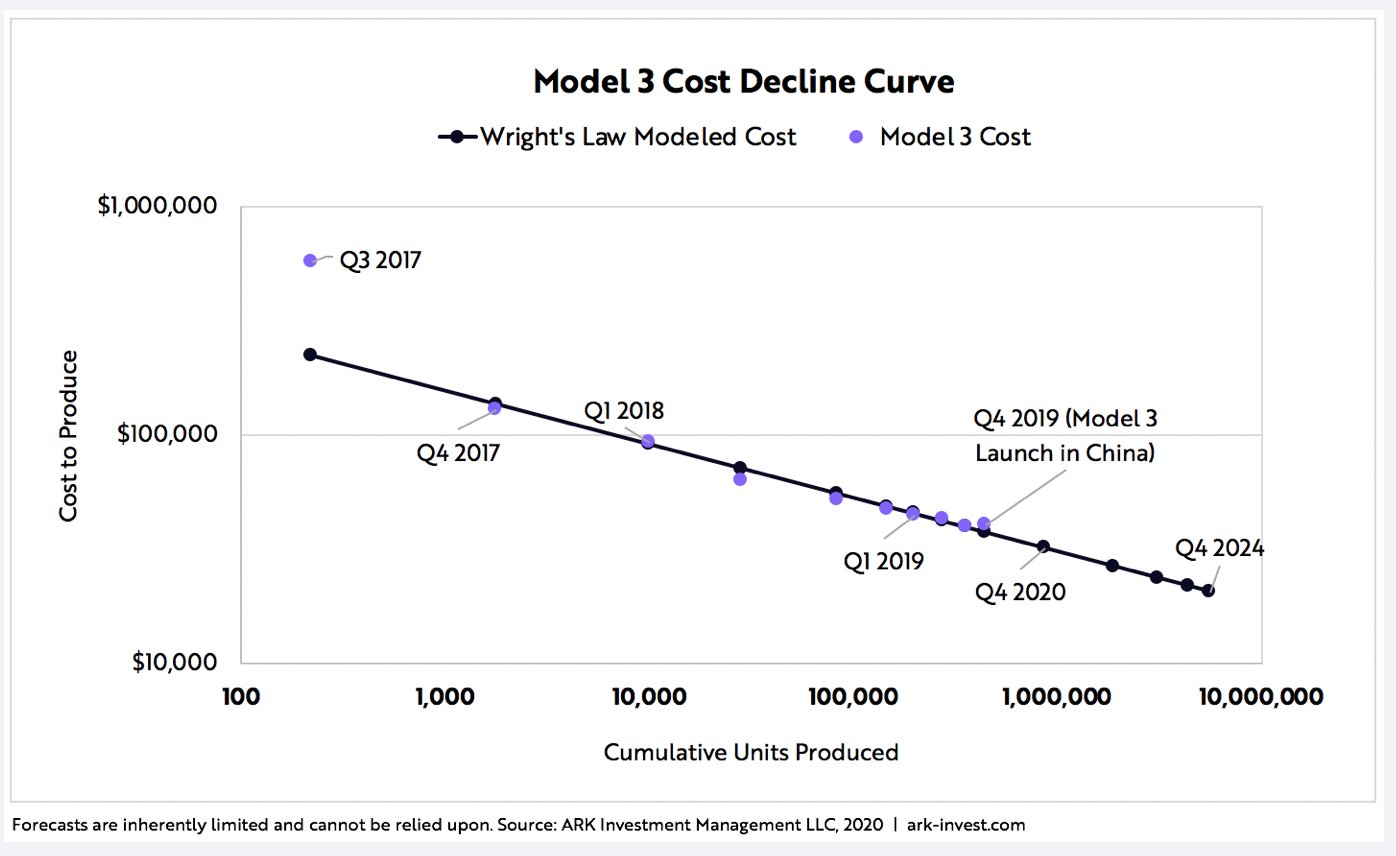

Bad graphs using straight lines are an important

special case. Here are some examples from

ARK:

I've seen such graphs projecting Li-ion battery prices falling down to $15/kWh, which makes no physical sense, and battery prices are up in 2022 rather than down. As for Tesla, any new Tesla Model 3 is now >$48000, and you won't actually receive a car any time soon unless you get high-margin add-ons.

Well, I can draw straight lines in a box too.

As you can see, the line goes up and to the right. The implications are clear.

And yet, you need to use some numbers to make decisions. When the news and PR releases and scientific papers all lie to you, what can you do?

- Find

multiple charts and compare them.

- Look for data that shows underlying

details for different components.

- Know enough technical details that

you can tell when someone gets some of them wrong.

-

Look for

info that contradicts your view, not just info that confirms it.

- Consider incentives

for being right and wrong. If someone tells you wrong things about, say,

Iraq having a nuclear program, does that help or hurt their career?

#5: too many new things

There once was a startup that wanted to store energy by putting compressed air in composite tanks. I had the following conversation with someone there:

me: Composite

tanks are too expensive for this to be feasible.

them: We'll make cheaper

ones.

me: If you can make cheaper ones, then start by just selling those.

If doing one new thing would be a business, then don't add extra risks

to that before it's even validated.

To be fair, their investors

wanted to invest in grid energy storage, not gas tank manufacturing, and

expected them to generate intellectual property rather than profits. When a

company is doing something that seems silly, financiers often made that

decision for them. (So the investors should have done better technical

evaluation, right? No, they did relatively extensive due diligence by Top

People, while most venture capitalists don't want to look at technology

details at all, but those Top People made some of the above mistakes.)

#6: starting too far from viability

If a process is used

now, then even a small improvement is useful. If a process is 10x too

expensive now, then it needs to be improved more than 10x to maybe be

worthwhile, and even then, it will be harder to switch customers to

something new.

Does a 20x improvement in a technology happen

sometimes? Yes, but a smaller improvement is more likely, and some startup

founders don't consider the amount of improvement needed very much.

At the same time, processes currently used on a large scale have usually

been thoroughly investigated. So, if you're making a startup, all else being

equal, it's often best to pursue something that's almost economically

competitive.